By Sadagopan Iyengar, Coimbatore

There are any number of works chronicling the life and times of Sri Rama. After the advent of Valmiki’s glorious work, the first and foremost among epics (Aadi Kaavyam), poets over the ages, learned and not-so-learned, have deemed it their pleasurable duty to retell the story of Rama in their own words. Thus were born the Ananda Ramayanam, the Adbhuta Ramayanam, Kamba Ramayanam, Rama Naatakam, etc., each having its own unique flavour and colour. Of all these, however, we accept the Valmiki Ramayanam as the correct and complete version of Rama’s eternal story, not because of its chronological superiority or literary value, but principally due to the fact that Valmiki’s was an eye-witness account. Blessed by Brahma, Valmiki had the unique advantage of divine vision, (sarvam viditam te bhavishyati) which enabled him to perceive and put to paper whatever happened to Sri Rama and His cohorts, exactly as it happened. Whether the events occurred in private between two individuals or in public, Valmiki was able to see the same in all their exquisite detail and recount them in words dripping with devotional fervour garbed in prolific poetry.

However, rather puzzlingly, we find that Valmiki has omitted certain events from his magnum opus. And how do we come to know of this? If we say that there have been omissions, the presumption is that these episodes are found in another version, equally if not more authentic than the Valmiki Ramayanam. Certain events are chronicled by Azhwars, those apostles blessed with unblemished wisdom (mayarvara madinalam) by the Lord Himself, which we do not come across in Valmiki’s version. Since Azhwars’ outpourings are paramount for us, we have to conclude that these events have been omitted by Valmiki for some reason best known to himself and which we, with our feeble intellects, are unable to divine at this point in time, millennia after the occurrences. Examples of such events are to be found in Periazhwar Tirumozhi, where Azhwar speaks of Sita Devi having tied up Sri Rama with garlands of jasmine (Malligai maamaalai kondu angu aarttadum or adayaalam).

There is a similar event, an extremely heartening one and one which has inspired millions, narrated by Sri Tondaradippodi. Though this is a popular story and known even to children, it is indeed worth recounting for its beautiful content. Here is the Tirumaalai paasuram chronicling the contribution of the Squirrel—

Kurangugal malayai nookka kulittu taam purandittu odi

Taranga neer adaikkaluttra chalamilaa Anilum polen

Marangal pol valiya nenjam vanjanen nenju tanaale

Aranganaarkku aatcheyyaade aliyatten ayarkkindrene

This paasuram deals with what we may characterize as the cornerstone of our Sampradayam, viz., “Kainkaryam” or service. Service to the Lord and His devotees is the paramount reason for our very existence, according to Acharyas. However, if you stop to consider this for a moment, we are plagued by a huge doubt: the Lord is a perfectly complete entity, lacking nothing. He is a person of absolutely satisfied desires—avaapta samasta kaaman–who really doesn’t need anything. Under the circumstances, what service can we really perform for Him? Further, if you consider His stature as the Supreme Entity and our own as insignificant cogs in the giant wheel of His creation, there doesn’t appear to be anything at all which we are capable of doing, which would tantamount to service to Him. Ammaan Aazhippiraan avan evvidatthhan yaan aar? Despairs Sri Nammazhwar, comparing Emperuman’s exalted status with our own inconsequential existence. This being so, of what earthly use can we be to Him and what can we possibly do that can be honestly termed service?

This paasuram deals with what we may characterize as the cornerstone of our Sampradayam, viz., “Kainkaryam” or service. Service to the Lord and His devotees is the paramount reason for our very existence, according to Acharyas. However, if you stop to consider this for a moment, we are plagued by a huge doubt: the Lord is a perfectly complete entity, lacking nothing. He is a person of absolutely satisfied desires—avaapta samasta kaaman–who really doesn’t need anything. Under the circumstances, what service can we really perform for Him? Further, if you consider His stature as the Supreme Entity and our own as insignificant cogs in the giant wheel of His creation, there doesn’t appear to be anything at all which we are capable of doing, which would tantamount to service to Him. Ammaan Aazhippiraan avan evvidatthhan yaan aar? Despairs Sri Nammazhwar, comparing Emperuman’s exalted status with our own inconsequential existence. This being so, of what earthly use can we be to Him and what can we possibly do that can be honestly termed service?

Sri Periavaacchaan Pillai tells us that such an attitude, of refraining from doing anything in the nature of Kainkaryam simply because it may not behoove the Lord’s status, is totally wrong—Namakku ulla gnaana saktigalai kondu Poornanukku naam ondru seigaiyaavadu en? endru kai vaangumavargal bhaagya heenargal. As eternal servitors of the Lord, the whole raison d’ etre of our existence is to please the Paramatma. When we say that the Lord is a person of satisfied desires, this completeness in Him arises out of His propensity to be satisfied with what little we have to offer, despite however insignificant it is. He looks not at how little or inconsequential our offering is, but the depth of devotion with which it is accompanied. It is this beautiful tenet that is demonstrated by the episode of The Little Squirrel.

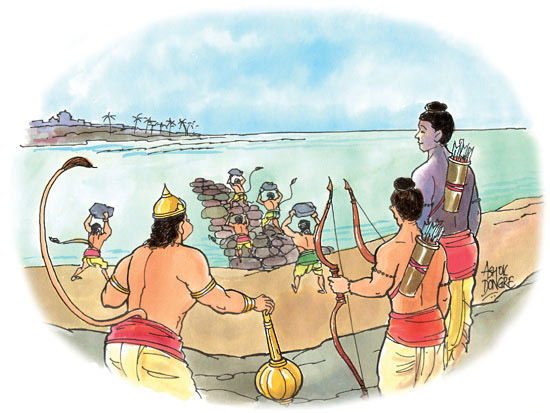

The entire army of vanara veeras was busy building the bridge across the ocean, under the directions of Nala. Thousands of monkeys spread out all over the coastal mountains and forests. They uprooted whole mountains, huge boulders and towering trees and carried them with considerable effort to the shore. Other vanaras standing on the shore took over these heavyweights from the carriers and flung them into the ocean. Nala stood at the site supervising the construction and ensuring that the hillocks and rocks fitted together to form a smooth pathway for the army to cross over to Lanka. Sri Rama, who was watching from a distance, witnessed the bridge taking shape slowly but surely. Raghava’s benign glance fell on a vanara carrying a mountain twice as big as himself and the vanara was overjoyed at it , so much so that on his return journey he carried two such mountains, enthused by Sri Rama’s fleeting look. Such was the spirit and motivation with which the vanara veeras undertook the stupendous effort of bridging the vast waters.

A small squirrel was watching the exercise from a distance, wary of getting run over by the monkeys, who were in a tearing hurry. However, it appeared to the squirrel that the monkeys were not doing things at a fast pace. (Whenever we are onlookers to some difficult task being undertaken, don’t we always feel that those engaged in the endeavour are doing things either slowly or improperly and that we ourselves would have done a much better job?). The squirrel thought, “At this speed, the bridge wouldn’t be built even after six months. When would the bridge be completed, when would Chakravartthi Tirumagan be able to cross over to Lanka and when would Piratti, pining away for her Lord, be reunited with Him? Things are going too slow for words!”. Here are the emotive words of the commentator of the Tirumalai paasuram, portraying the Squirrel’s impatience eloquently—Perumaalukku aatraamai karai puralaa nirkka, mudaligalukku ittanai mettanavellaam en taan? irundapadiyaal chadakkena kadal adaikkiravargalukku sakti illai: “These monkeys lack the strength and speed to rise to the occasion and get the bridge ready in record time for the impatient Lord to cross over” felt the Squirrel. “We should function with such speed that Sri Rama is able to have today’s lunch itself at the shores of Lanka after crossing over” the impudent Squirrel exhorted the astounded monkeys. Impatient for the divine reunion to happen at the earliest, the squirrel decided to take a personal hand in the affairs, to speed up things.

A small squirrel was watching the exercise from a distance, wary of getting run over by the monkeys, who were in a tearing hurry. However, it appeared to the squirrel that the monkeys were not doing things at a fast pace. (Whenever we are onlookers to some difficult task being undertaken, don’t we always feel that those engaged in the endeavour are doing things either slowly or improperly and that we ourselves would have done a much better job?). The squirrel thought, “At this speed, the bridge wouldn’t be built even after six months. When would the bridge be completed, when would Chakravartthi Tirumagan be able to cross over to Lanka and when would Piratti, pining away for her Lord, be reunited with Him? Things are going too slow for words!”. Here are the emotive words of the commentator of the Tirumalai paasuram, portraying the Squirrel’s impatience eloquently—Perumaalukku aatraamai karai puralaa nirkka, mudaligalukku ittanai mettanavellaam en taan? irundapadiyaal chadakkena kadal adaikkiravargalukku sakti illai: “These monkeys lack the strength and speed to rise to the occasion and get the bridge ready in record time for the impatient Lord to cross over” felt the Squirrel. “We should function with such speed that Sri Rama is able to have today’s lunch itself at the shores of Lanka after crossing over” the impudent Squirrel exhorted the astounded monkeys. Impatient for the divine reunion to happen at the earliest, the squirrel decided to take a personal hand in the affairs, to speed up things.

The squirrel went to the sea, dipped its tiny body in the waters, came back to the shore, rolled in the sand to get as much of the particles as possible entrapped in its bushy coat, went again to the waters and dipped again, thereby consigning the sand particles to the sea. This, the squirrel thought, would enable to bridge the gaps between the mountains and boulders, the sand particles acting as a bonding agent. Little did it think of the infinitesimal quantity of sand that would stick to its diminutive body and the fact that the sand particles would hardly make any difference to the process of construction. The squirrel’s idea was that if it repeated this process of dipping and rolling often enough, a huge quantity of sand could be carried into the sea, with which the rocks and boulders of disparate sizes and shapes could be bonded together. Having conceived of this audacious but admirable plan, the Squirrel put it immediately into action, running back and forth carrying minuscule quantities of sand and dumping them into the waters. It did realize that the quantity it was able to carry per trip was not much, but it planned to compensate the same by the number of trips it could make.

The Squirrel did not stop to think as to what possible difference its effort could make to the mammoth endeavour of bridging the ocean, nor did it feel discouraged by its own diminutive size and strength, vis-à-vis those of the vanara veeras. Inspired by the sole thought of service to Sri Rama and wishing to contribute its mite to the grandiose plan of marching to Lanka, the Squirrel went ahead, bathed, rolled in the sand, scooted to the waters, dumped the sand and came back for more. Back and forth, back and forth went the squirrel, unmindful of how its activity looked to the others engaged in the effort and totally oblivious to whether or not Sri Rama took cognizance of it. (As we know only too well, when the boss is present and watching, even those who otherwise hardly lift a little finger, give the impression of toiling hard, to impress the boss. The Squirrel, however, was totally unaware of such enlightened “management” techniques).

When you come to think of it, the job undertaken by the Squirrel was much riskier than that of the monkeys: with its puny body, the Squirrel could easily have been run over by the monkeys: when it dipped into the waters for dumping the sand it carried, it could have well been washed away by a strong wave. All these, however, didn’t occur to the Squirrel and if they did, it just ignored them and carried on its kainkaryam indefatigably, with singular focus on the rather ambitious goal it had set for itself. Further, the Squirrel also felt, says Sri Pillai, that if it dipped in to the sea enough number of times and carried off the water ashore, the sea would also eventually dry up, obviating the necessity for a bridge!-ipprakaarattaale kadalai toorpom endru paarttu neer suvarum manalum kondu varalaam endraaittu ninaivu!

When you come to think of it, the job undertaken by the Squirrel was much riskier than that of the monkeys: with its puny body, the Squirrel could easily have been run over by the monkeys: when it dipped into the waters for dumping the sand it carried, it could have well been washed away by a strong wave. All these, however, didn’t occur to the Squirrel and if they did, it just ignored them and carried on its kainkaryam indefatigably, with singular focus on the rather ambitious goal it had set for itself. Further, the Squirrel also felt, says Sri Pillai, that if it dipped in to the sea enough number of times and carried off the water ashore, the sea would also eventually dry up, obviating the necessity for a bridge!-ipprakaarattaale kadalai toorpom endru paarttu neer suvarum manalum kondu varalaam endraaittu ninaivu!

Because of its enthusiasm for kainkaryam, the Squirrel realized not that the amount of water or sand it could displace depended not on its grandiose intentions, but on its small physical body, and carried on enthusiastically. Further, by running fast in its endeavour to make more trips to the ocean, the Squirrel forgot that what little sand adhered to its body would fall off during the tumultuous run to the sea, defeating the very purpose of its efforts. Azhwar expresses surprise at the audacity of the small Squirrel in attempting to bridge the vast waters of the ocean—taranga neer adaikkaluttra chalam ilaa anilum polen. The Squirrel’s intentions and actions were characterized by the highest degree of sincerity, says Azhwar—Chalam ilaa Anil. Such was the Squirrel’s involvement that it imagined itself to be the principal workman, with the monkeys as mere assistants!—kadal adaikkiraargal taangalaai, mudaligalum tangalukku edutthu kai neettugiraargal taangalaai aaytthu ivattrinudaya abhimaanam.

Though the term “Kulitthu” refers to the squirrel taking a dip in the ocean so that sand would stick to its body, we cannot help but think that it might have tried to purify itself with Samudra snaanam, before participating in Bhagavat Kainkaryam. When you consider that the Squirrel was not endowed with a reasoning intellect to prompt performance of kainkaryam nor a deep knowledge of Shastras to divine the importance of kainkaryam, nor even with the usual complement of limbs with which to perform kainkaryam, its conduct on the occasion becomes exemplary and worth emulation. It appears to have acted solely based upon a fervent desire to aid Sri Rama’s cross over to Lanka at the earliest.

The monkeys who were lifting great weights on their shoulders and arms, found the behavior of the Squirrel puzzling initially. And when they realized that the Squirrel was trying to bridge the ocean with its wasteful effort, they could hardly control their mirth. Such a little animal, with a body hardly six inches long, trying to emulate strong and sinewy monkeys who were as big as the mountains they were carrying! The monkeys burst into great guffaws of laughter at the antics of the Squirrel. They pointed out the Squirrel to their companions and made hearty fun of the tiny animal and its apparently mindless but frenetic activity.

When the commotion and hilarity of the vanara veeras caught His attention and He came to know of the reason, Sri Rama sent Lakshmana to fetch the brave squirrel, which was holding its own against the taunts of the monkeys. Even when Lakshmana tried to catch hold of it, the Squirrel turned away and made one more trip to the ocean with the sand it had gathered in its coat. At last Lakshmana caught it and brought it to the Prince of Ayodhya, who made the restive Squirrel sit on His lap and caressed its back, to relieve it of the enormous physical stress and strain it had undergone in His service. Folklore has it that these lines of caress, representing the imprint of the Prince’s fingers on the Squirrel’s back, are to be seen even today on the backs of its descendants, several millennia after the event, as a reminder to mankind of the exemplary service performed by their ancestor.

Quantitatively speaking, the squirrel’s material contribution to the bridge was insignificant, even though it represented an epitome of effort for him. Hence, as far as the construction was concerned, it did not matter even an iota: however, to the Prince of Ayodhya, it mattered quite a lot, for what counted was the purity of purpose and intensity of intention—bhaava shuddhi—and not the quantum of contribution. So too is it in all things spiritual.

When you are determined to do something, your own handicaps or disabilities would hardly be an obstacle—ruchiyaanadu tam taam alavai paarkka ottaadire. The Squirrel’s audacious penchant and apparently indefatigable energy for kainkaryam, with scant regard for its own puniness and limited wherewithal, are lofty models for our emulation. It teaches several vital lessons to aspirants for kainkaryam: not to be daunted by the task, however stupendous it may appear to be, not to be put off by one’s apparent incapacity and more than anything else, not to play the escapist by shrugging off with “What difference is my minuscule contribution going to make!”

Srimate Sri LakshmiNrisimha divya paduka sevaka SrivanSatakopa Sri Narayana Yatindra Mahadesikaya nama: